Where's Tim?

Crickets

Hello Friends,

Okay—picture this. Let’s suppose you are looking for me. How would you find me?

I’ll use a trivial example: assume we live in the same town.

To find me, you’d have to ask around (since telephone books are a thing of the past—remember when anyone’s address was available for free and no one bothered you?).

You could ask the shady-looking guy who hangs out in the park—but can you trust him? He could send you on a Wild-Turkey-hazed wild-goose chase. Or worse, direct you down an alley where his buddies would steal your lunch money.

No, to actually find me, you would have to ask a trusted source. Trust is important in finding what you’re looking for.

For example, you could go to the post office. More than likely, the post office would have my official address. Assuming I’m not hiding my home address and using a PO box, you could just ask the post office person, “Where does David live and how do I get there?”

Bingo, in minutes, you’re knocking on my door. Hopefully, you brought donuts.

This scenario, finding something by asking a trusted source, is exactly how the Internet works.

When you type something into your browser, like “https://www.karmicrobot.com,” your browser finds my website to display. That happens because Chrome (or any browser) asks a trusted source to find me and connect you to my Substack.

On the Internet, this trusted source is known as the Domain Name System or DNS.

It is spread out across the Internet, like many post offices. It’s composed of domain name servers (computers) that keep the whole system updated. If a new website arrives on the internet, DNS servers update each other, so when you search for that new website, you find it.

It’s a fairly simple yet powerful system. Occasionally, if bad data gets into one DNS server, that bad data can spread through the system, like a shady character sending you down a dark alley.

Now, remember way back to last week when all kinds of people and businesses had problems connecting to each other on the Internet? That was because Amazon Web Services (AWS), a part of Amazon that hosts people’s websites, broke its DNS servers.

The result was just as if a bunch of post offices were closed—nobody could find anyone in those communities.

Unfortnately, AWS is so large and hosts so many of the world’s websites, the broken DNS issue was as if you got to the edge of the Eastern Seaboard of the US and found a locked gate with a sign that said, “No one lives here anymore.”

This went on for hours—all day, in fact. And hours is a long time in the Internet world, where people expect responses in milliseconds.

I’ve had a lot of experience with AWS. I’ve lived through a number of outages. This one seemed a little different… a little less orderly, took a little longer to resolve.

My first job as a professional programmer was before the Internet, before Amazon, before AWS and Facebook and Google were twinkles in their young founders’ eyes.

It was shortly after the breakup of the old Ma Bell phone system in America, during the rise of regional phone carriers and cellular phones (remember companies like Nextel, Sprint, and Qwest?).

I started programming at a company that created and maintained most of the world’s paging infrastructure—for you kids out there, people used to carry pagers like cellphones. A pager could only display block numbers and some alphabetical characters that could be interpreted from them—like an 8 being a B.

The original text messages were short “canned” messages that you could send to a loved one to be displayed on the most advanced pagers: “be home late,” “pick up kids,” “dinner in oven,” “I love you.”

The company I worked for was the king of pagers. It claimed that much of the world’s pager messages travelled through its systems. As evidence of how things change: today, the company is gone, my stock became worthless, and its website URL is for sale.

Back in the day, it was an old-timey software company, a great place to get my coding chops. Older guys who had been programming since the 70s ruled the roost, and they weren’t doing their job if they didn’t haze the junior programmers.

That was just how all business was back in those days. You had to earn your place.

The experienced workers were respected for what they knew, and what they knew was important because no one else had that knowledge—there wasn’t anything like Google or AI to get answers.

You had to talk to these guys. They were the gatekeepers. And you were glad for it, because they could solve a problem in minutes.

Whenever I ran up against a programming issue that I couldn’t solve myself, I’d go to my boss. Inevitably, he’d say, “Go see Tim.”

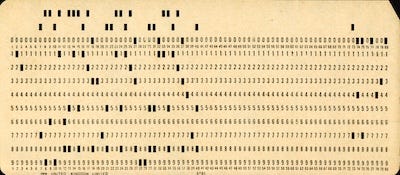

This both terrified and thrilled me. Tim was the original old-school programmer. He cursed the day keyboards replaced punched cards.

As a junior programmer, talking to Tim was setting yourself up for a day-long haze. But you knew that you’d be better for it when it was all over.

Peering over his cube wall, I’d say, “Hi Tim,” and wait for the look of contempt to greet me in response.

After a full two minutes, he’d stand and face me.

It was an orchestrated dance. Once he stood, I knew I could continue. “Kevin told me to ask you about X.”

It didn’t matter what X was, Tim always gave the same response: “Why do you want to know about that?”

And then he’d sit back down and return to his work.

He knew the entire system, built most of it, and anticipated what was needed to improve it. As soon as I asked my question, Tim knew exactly what I required, but he made me wait.

I would quietly leave to sit back at my desk and busy myself, hoping for the delivery of enlightenment, like a young boy on Christmas Eve.

Several hours later, Tim would show up at the doorway to my cube with a book. He’d hand it to me, and say, “Look at page 107.” It was exactly enough and just what I needed.

When I was done with my task, Tim would review my code and send me notes on improving it. Then, I’d be on to the next thing, and if I had done a good job, Tim would haze me a little less the next time.

That was just how it was done—before the Internet, before script kiddies with English degrees writing banking software, before AI vibe coding and CEOs thinking they can replace human intelligence with artificial intelligence.

Now, my peers and I have become the Tims in our respective arenas. Except, times have changed. Most people don’t use pagers, and no one has seen a punched card in years.

Junior developers spend days trying to solve problems on their own before coming to me (no matter how much I try to correct this habit). They waste time, search the Internet to find answers, and more and more, they use AI (to their own detriment).

The problem with this is that the specific institutional knowledge about a company’s particular system cannot be found on the Internet. It still lives in the old guys, like Tim. And now, me.

And that’s why it took so long for Amazon to fix the Internet last week. Old guys are leaving (or being forced out of, or fired from) the industry, taking the institutional knowledge with them.

Just a few years ago, if you asked a roomful of developers why something on the Internet wasn’t working, an old guy would stand up and say, “It’s probably DNS.”

Old guys inherently know that problems on the Internet follow the philosophy of Occam’s Razor: the simplest, most obvious solution is probably the right one.

And DNS is at the heart of the Internet. A network issue is most likely one thing not being able to find another thing, which is a DNS issue.

Young developers haven’t gained the experience to discern a simple solution from a complicated, inefficient one.

Fittingly, upon analysis, it was AWS’s automated DNS system that was to blame. Essentially, a non-human process broke their DNS, and there was no one in the room to stand up and say, “It’s probably DNS.”

Someone, perhaps many rooms of someones, had to figure this out from scratch.

That takes time, costs businesses money, annoys users, and affects reputations. Its actual financial implications are potentially way more than a couple of old guys’ salaries.

Just remember when you knock on my door, have donuts.

Happy reading, happy writing, happy looking for something you might not find,

David

A very fun story with some learning along the way. I like the way David cleaves to his mission with Karmic Robot, and the wonderful writing. I look forward to these stories and can't stop reading once I start.

Thanks Rae! I'm glad you read and I'm glad you enjoy.