Big Daddy Data

It's All Just Numbers

My favorite car, a 1986 Nissan Pulsar hatchback, survived the Perfect Storm on Halloween in 1991 parked outside my apartment on Short Beach in Revere, Massachusetts. It was nibble, comfortable, and light enough to push out of a snowbank. It was sold when I left Boston and moved to Atlanta in 1992.

While in Georgia, I bought my second most favorite car, a gray 1974 Toyota Corona station wagon. I paid $400 for it, and it had over 260,000 miles on the odometer, crank windows, no A/C, and an AM radio.

It also had a sticker on the bumper with a saying in a language I didn't know—German or Swedish. The guy I bought it from said his wife added the bumper sticker when he purchased the car.

He told me it loosely translated to: Don't drive faster than your angels can fly. It was the first time I had heard that saying.

And (ironically?), my angels would have to be pretty slow for me to outrun them in that car.

As I recently purchased a new car, my mind has returned to that quote. I Googled it.

Surprisingly, there aren't many references to it—mostly car and motorcycle clubs. A few mentions of addiction groups. Nothing definitive. And I didn't find it cited in any other languages besides English.

I swear I used to see that saying on bumper stickers and coat pins often in the 1990s. Once I heard it the first time, I saw it everywhere. At least, that's how I remember it.

Google's search AI, Gemini, reported that its origin is under debate, but the saying is loosely attributed to Mother Teresa. Gemini also didn't give me any other references. I'm not sure how something with only one answer can be debatable.

The whole thing got me thinking of another saying, ironically also loosely attributed, this time to Winston Churchill: History is written by the victors.

Google's AI had a little more to report on this quote, suggesting that it could also have been constructed out of comments made at the Nuremberg Trials or an Athenian general named Thucydides who fought in (and lost) the Peloponnesian War (sour grapes?).

This second quote's sentiment made me wonder about my memory of the first quote. So much so that I started questioning whether my 1974 Toyota had that sticker on it at all.

Had I hallucinated it?

Was that bumper sticker actually on someone else's car? Was it even in a foreign language? Searching the Internet, using a combination of AI and Google, couldn't give me evidence I hadn't misremembered the whole thing.

What was my history?

Stepping a little deeper into the conspiracy doggy-doo,… what if my searching experience has been completely mediated? Who are the victors writing my history? Answering on Google?

Are there even victors? Or is it all just random information?

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, admits that AI has a particular type of problem:

… [AIs were] incentivized to guess rather than admit they simply don't know the answer.

How many people do you know who do this? It's a human trait.

And then, thinking about it… when is our history / memories not mediated by social media, other people, television, etc. Perhaps, I'm just suggesting that we need to recognize that experience, in general, in life.

It's well known that two people will get different, personalized results when they search the same subject in a search engine. That's a side-effect of online advertising targeting methods.

Not only will you see different ads, but you will also see different articles.

It's exactly like a low-level comic getting a crowd in the mood for the headliner; search responses are designed to put you in the mood to buy from those advertisers who pay the search engine to find buyers. It's a symbiotic system that works against your wallet.

Not just our history, but our real-time experiences are mediated. This is not new. Manipulation is as old as the Garden of Eden.

What gives me pause is how it's being done today. Just as the tech terms AI, cryptocurrency, and blockchain have become part of our vernacular, the somewhat vague term, Big Data, has found its way into our every-day dialogue.

Big Data represents all the little bits of information that have been collected about you, your habits, your activities, your desires, your disappointments. Considering the public (and not-so-public) lives of almost everyone, you can imagine it's a lot of data. Big, in fact.

But that's just it; it's data—numbers.

The data in Big Data are rows and columns in enormous spreadsheets and databases and charts and graphs and all kinds of things that computers can read to crunch it and come up with some answer—who will buy a car this month? What is the best way to get 50-year-olds to buy a car? What words can be employed to intimidate a 50-something guy into purchasing an extended warranty?

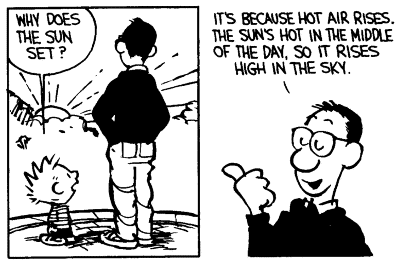

A subtle downside of the fact that data now rules our lives is an observation I've been making more and more over the last few years: as our society has become increasingly data driven, more represented and interpreted in abstract numbers, people have lost the ability to read and interpret non-data, physical stuff.

Young adults today struggle to tell time on an analog clock, to navigate with a paper map, to, basically, orient themselves by their surroundings based on sensory input.

When faced with any issue, 999 out of a 1000 young adults (and a growing number of us aged adults) go straight to their cellphones for answers, and recently, to Mister or Miss Chat, rather than looking up and around their environment.

Yesterday, while running an errand in an unfamiliar town, I got lost. Not because I didn't know where I was going, but because I was trusting my GPS. It kept flipping on me, telling me I was passing my destination every time I turned back towards it. Seems that the problem was that the destination that I was looking for was not a real place, but rather a collection of data that looked like a place to Google Maps.

Eventually, I put my phone in my pocket and looked around. I saw an intersection with cars; I saw train tracks; I saw people. I knew where I came from and had a relative sense of which direction I wanted to go. With a little common sense and a few brief inquiries of my fellow humans, I found my way.

I don't think my angels live in my mobile phone.

Happy reading, happy writing, happy orienteering,

David